Period IV: Winning the Saracens? A.D. 1200-1600

The fourth period began with a spectacular, new evangelistic instrument-the Friars-and after the disaster of the prolonged plague would end with the greatest, the most vital, and most disruptive reformation of all. However, the Christian movement had already been involved for a hundred years in the most massive and tragic misconstrual of Christian mission in all of history. Ironically, part of the “flourishing” of the faith toward the end of the previous period led to disaster: never before had any nation or group of nations in the name of Christ launched as energetic and sustained a campaign into foreign territory as did Europe in the tragic debacle of the Crusades. This was in part the carry-over of the Viking spirit into the Christian Church. All of the major Crusades were led by Viking descendants.

While the Crusades had many political overtones (they were often a unifying device for faltering rulers), they would not have happened without the vigorous but misguided sponsorship of Christian leaders. They were not only an unprecedented blood-letting to the Europeans themselves and a savage wound in the side of the Muslim peoples (a wound which is not healed to this day), but they were a fatal blow even to the cause of Greek/Latin Christian unity and to the cultural unity of eastern Europe. In the long run, though Western Christians held Jerusalem for a hundred years, the Crusaders by default eventually gave the Eastern Christians over to the Ottoman Sultans. Far worse, they established a permanent image of brutal, militant Christianity that alienates a large proportion of mankind, tearing down the value of the very word Christian in missions to this day.

Ironically, the mission of the Crusaders would not have been so appallingly negative had it not involved so high a component of abject Christian commitment. The great lesson of the Crusades is that goodwill, even sacrificial obedience to God, is no substitute for a clear understanding of His will. Significant in this sorry movement was an authentically devout man, Bernard of Clairvaux, to whom are attributed the words of the hymn Jesus the Very Thought of Thee. He preached the first crusade. Two Franciscans, Francis of Assisi and Raymond Lull, stand out as the only ones in this period whose insight into God’s will led them to substitute for warfare and violence the gentle words of the evangel as the proper means of extending the blessing God conferred on Abraham and had always intended for all of Abraham’s children-of-faith.

At this point we must pause to reflect on this curious period. We may not succeed, but let us try to see things from God’s point of view, treading with caution and tentativeness. We know, for example, that at the end of the First Period after three centuries of hardship and persecution, just when things were apparently going great, invaders appeared and chaos and catastrophe ensued. Why? That followed the period we have called the “Classical Renaissance.” It was both good and not so good. Just when Christians were translating the Bible into Latin and waxing eloquent in theological debate, when Eusebius, as the government’s official historian, was editing a massive collection of previous Christian writings, when heretics were thrown out of the empire (and became, however reluctantly, the only missionaries to the Goths), when Rome finally became officially Christian… then suddenly the curtain came down. Now, out of chaos God would bring a new cluster of people groups to be included in the “blessing,” that is, to be confronted with the claims, privileges, and obligations of the expanding Kingdom of God.

Similarly, at the end of the Second Period, after three centuries of chaos during which the rampaging Gothic hordes were eventually Christianized, tamed and civilized, Bibles and biblical knowledge proliferated as never before. Major biblical-missionary centers were established by the Celtic Christians and their Anglo-Saxon pupils. In this Charlemagnic renaissance, thousands of public schools led by Christians attempted mass biblical and general literacy. Charlemagne dared even to attack the endemic use of alcohol. Great theologians tussled with theological/political issues, The Venerable Bede became the Eusebius of this period (indeed, when both Charlemagne and Bede were much more Christian than Constantine and Eusebius). And, once again, invaders appeared and chaos and catastrophe ensued. Why?

Strangely similar, then, is the third period. In its early part it only took two and a half centuries for the Vikings to capitulate to the “counterattack of the Gospel.” The “renaissance” ensuing toward the end of this period was longer than a century and far more extensive than ever before. The Crusades, the cathedrals, the socalled Scholastic theologians, the universities, most importantly the blessed Friars, and even the early part of the Humanistic Renaissance make up this outsized 1050-1350 outburst of a Medieval Renaissance, or the “Twelfth Century Renaissance. But then suddenly a new invader appeared-the Black plague-more virulent than ever, and chaos and catastrophe greater than ever occurred. Why?

Was God dissatisfied with incomplete obedience? Or was Satan striking back each time in greater desperation? Were those with the blessing retaining it and not sufficiently and determinedly sharing it with the other nations of the world? More puzzling, the plague that killed one-third of the inhabitants of Europe killed a much higher proportion of the Franciscans: 120,000 were laid still in Germany alone. Surely God was not trying to judge their missionary fire. Was He trying to judge the Crusaders whose atrocities greatly outweighed the Christian devotional elements in their movement? If so, why did He wait several hundred years to do that? Surely Satan, not God, inflicted Christian leadership in Europe so greatly would not Satan rather have that happen than for the Crusaders to die of the plague?

Perhaps it was that Europe did not sufficiently listen to the saintly Friars; that it was not the Friars that went wrong, but the hearers who did not respond. God’s judgment upon Europe then might have been to take the Gospel away from them, to take away the Friars and their message. Even though to us it seems like it was a judgment upon the messengers rather than upon the resistant hearers, is this not one impression that could be received from the New Testament as well? Jesus Himself came unto His own, and His own received Him not, yet Jesus rather than the resisting people went to the cross. Perhaps Satan’s evil intent - of removing the messenger - God employed as a judgment against those who chose not to hear.

In any case, the invasion of the Bubonic plague, first in 1346 and every so often during the next decade, brought a greater set-back than the Gothic, the Anglo-Saxon or the Viking invasions. It first devastated parts of Italy and Spain, then spread west and north to France, England, Holland, Germany and Scandinavia. By the time it had run its course 40 years later, one third to one half of the population of Europe was dead. Especially stricken were the Friars and the truly spiritual leaders. They were the ones who stayed behind to tend the sick and to bury the dead. Europe was absolutely in ruins. The result? There were three rival Popes at one point, the humanist elements turned menacingly humanistic, peasant turmoil (often based in justice and even justified by the Bible itself) turned into orgies and excesses of violence. “The god of this world” must have been glad, but out of all that death, poverty, confusion and lengthy travail, God birthed a new reform greater than anything before it.

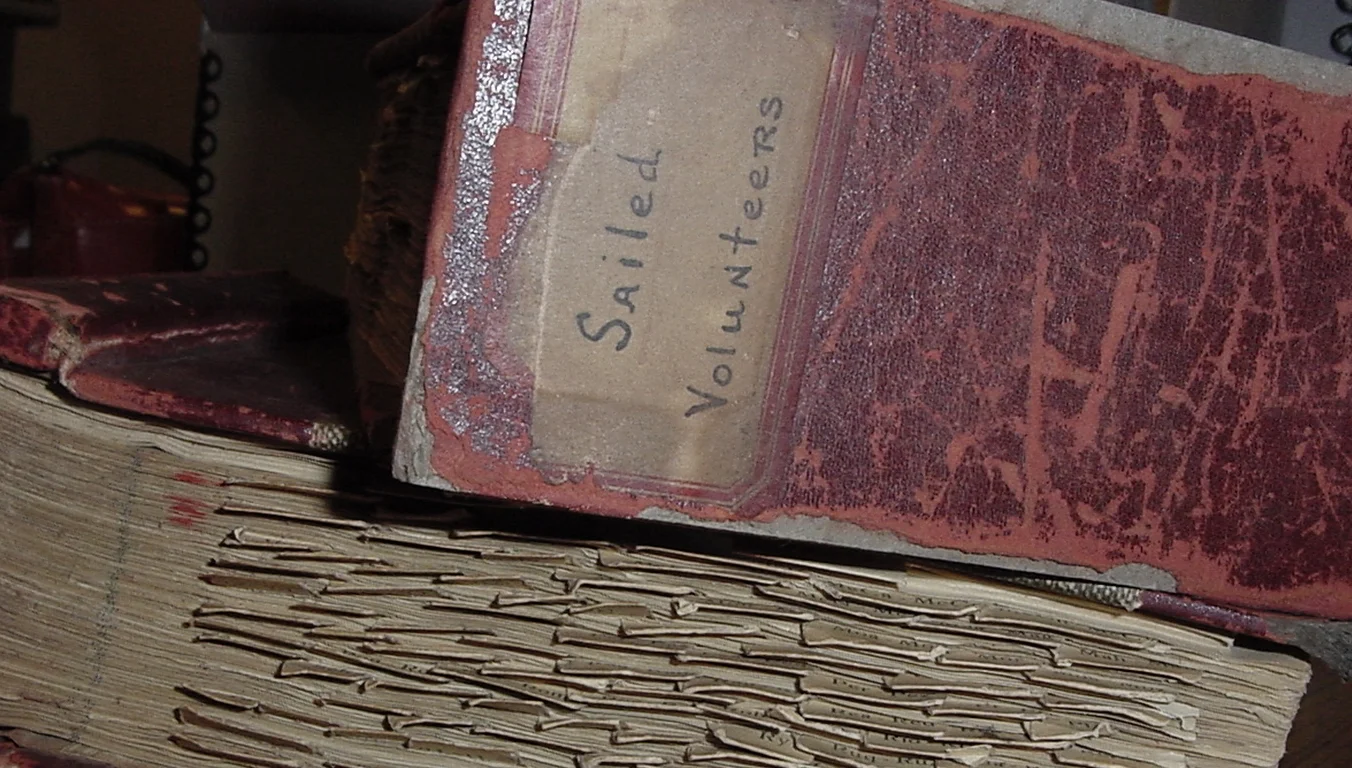

Once more, at the end of one of our periods, a great flourishing took place. Printing came to the fore, Europeans finally escaped from their geographical cul de sac and sent ships for commerce, subjugation and spiritual blessing to the very ends of the earth. And as a part of the reform, the Protestant Reformation now loomed on the horizon: that great, seemingly permanent, cultural decentralization of Europe.

Protestants often think of the Reformation as a legitimate reaction against the evils of a monstrous Christian bureaucracy sunken in decadence and corruption. But it must be admitted that this reformation was much more than that. This great decentralization of Christendom was in many respects the result of an increasing vitality which-although this is unknown to most Protestants-was just as evident in Italy, Spain and France as in Moravia, Germany and England. Everywhere we see a return to a study of the Bible and the appearance of new life and evangelical preaching. The Gospel encouraged believers to be German, not merely permitted Germans to be Roman Christians. Nevertheless, that marvelous insight was one of the products of a renewal already in progress. (Luther produced not the first but the fourteenth translation of the Bible into German.) Unfortunately, the marvelous emphasis on justification by faith-which was preached as much in Italy and Spain as in Germany at the time Luther loomed into view-became identified and ensnarled with German nationalistic (separatist) hopes and was thus, understandably, suppressed as a dangerous doctrine by political powers in Southern Europe.

It is merely a typical Protestant misunderstanding that there was not as much a revival of deeper life, Bible study and prayer in Southern Europe as in Northern Europe at the time of the Reformation. The issue may have appeared to the Protestants as faith vs. law, or to the Romans as unity vs. division, but such popular scales are askew because it was much more a case of over reaching Latin uniformity vs. national and indigenous diversity The vernacular had to eventually conquer.

While Paul had not demanded that the Greeks become Jews, nevertheless the Germans had been obliged to become Roman. The Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians had at least been allowed their vernacular to an extent unknown in Christian Germany was where the revolt then reasonably took place. Italy, France, and Spain, which were formerly part of the Roman Empire and extensively assimilated culturally in that direction, had no equivalent nationalistic steam behind their reforming movements and thus became almost irrelevant in the political polarity of the scuffle that ensued.

However - here we go again - despite the fact that the Protestants won on the political front, and to a great extent gained the power to formulate anew their own Christian tradition and certainly thought they took the Bible seriously, they did not even talk of mission outreach. Rather, the period ended with Roman Europe expanding both politically and religiously on the seven seas. Thus, entirely unshared by Protestants for at least two centuries, the Catholic variety of Christianity actively promoted and accompanied a world-wide movement of scope unprecedented in the annals of mankind, one in which there was greater Christian missionary awareness than ever before. But, having lost non-Roman Europe by insisting on its Mediterranean culture, the Catholic tradition would now try to win the rest of the world without fully understanding what had just happened.

But why did the Protestants not even try to reach out? Catholic missionaries for two hundred years preceded Protestant missionaries. Some scholars point to the fact that the Protestants did not have a global network of colonial outreach. Well, the Dutch Protestants did. And, their ships, unlike those from Catholic countries, carried no missionaries. This is why the Japanese - once they began to fear the Christian movement Catholic missionaries planted-would allow only Dutch ships into their ports. Indeed, the Dutch even cheered and assisted the Japanese in the slaughter of the budding Christian (Catholic) community.