The Numbers

There is a distinction between the Jewish people and the religion of Judaism. Not all Jewish people consider themselves to be religious. Many profess to be atheists, agnostics, or secular. While not all Jewish people follow the religion of Judaism, when Jews choose to be religious, they generally choose some variety of Judaism rather than another religion. Judaism is considered “our” religion, available for those Jews who choose to adhere. In contrast, most Jewish people would consider Christianity to be “their” religion, that is, a religion appropriate for non-Jews.

With this in mind we can say that there are over 13 million Jewish people in the world today. Two surveys conducted by the Graduate Center of the City of New York found that Jews comprised 1.3% of the U.S. population, and 14% of Jews in the U.S. are secular. New York has the highest population of Jews with 1.75 million.

Jewishpeople.net gives the following population statistics as of 2002: of the over 13 million Jews in the world, 4.8 million are in Israel, over 6 million are in North America, 365,500 in South America, and Russia has 275,000.

Introducing Judaism

The term “Judaism” is sometimes loosely used to include not only the faith of modern Jews but also that of the Old Testament. Sometimes it is used to include the entire Jewish way of life. It is best, however, to use the term “Judaism” to refer to the religion of the rabbis that developed from about 200 B.C. onwards and crystallized following the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70. In this way Christianity is not described as a daughter religion of Judaism, but more correctly as a sister: both branched out from Old Testament faith.

The Development of Judaism

From around 200 B.C. onward, new institutions and ways of life developed that distinguished rabbinic Judaism from the religion of ancient (Old Testament) Israel. New institutions arose such as the synagogue (the house of worship and study), the yeshivot (religious academies for the training of rabbis), and the office of the rabbi (a leader holding religious authority).

One of the greatest catalysts in the development of Judaism was the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70, which meant the abolition of sacrifices and the priesthood. Rather than being guided by priests, prophets, or kings, the rabbis became the authorities who established various laws and practices that had normative authority.

Before the 18th century, there was basically one kind of Judaism. In contrast, one of the distinguishing features of modern Judaism is the existence of the three main movements or “branches.” These branches are not quite equivalent to what Christians understand by denominations, where one’s identity is often tied strongly to a particular denomination, and in which one’s affiliation is often determined simply by family tradition. The branches of Judaism are more like voluntary associations, with classifications according to cultural and doctrinal formulas (like denominations) but with adherence to a particular branch often governed by personal preference, nearness of a given synagogue, or one’s agreement with the rabbi’s style and views (like voluntary associations).

Within each branch you will find adherents with varying degrees of observance. Many Jewish people formulate their own informal version of Judaism, and do not fit exactly into any one of these categories. Nevertheless, knowing the distinctions between the branches and to which branch your Jewish friends adhere can be helpful in most witnessing situations.

Orthodox Judaism

There was only one kind of Judaism until the Age of the Enlightenment in the 18th century. Only later, to differentiate it from the other branches of Judaism, was this called “Orthodox.” Today, Orthodox Judaism is characterized by an emphasis on tradition and strict observance of the Law of Moses as interpreted by the rabbis.

Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism began in Germany in the 18th century at the time of the Enlightenment, or Haskalah. It sought to modernize what were considered outmoded ways of thinking and doing and to thus prevent the increasing assimilation of German Jewry. Reform Judaism emphasizes ethics and the precepts of the prophets.

Conservative Judaism

This branch developed from 19th-century German roots as a middle ground branch.

How to Think about the Three Branches

It can be helpful to compare Orthodox Judaism with Roman Catholicism or Greek Orthodoxy, where there is a heavy emphasis on tradition. Reform Judaism can be compared with Unitarianism, emphasizing humanism. Conservative Judaism can be compared to modern liberal Protestantism, emphasizing form over doctrinal content.

Notice that there is no equivalent to evangelical Christianity, emphasizing a personal relationship with God. Orthodox Judaism is sometimes mistaken for this, but it is more concerned with living according to the traditional understandings than with a personal relationship with God.

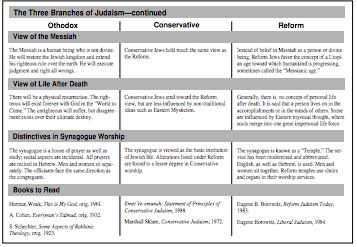

The “Three Branches of Judaism” chart on page three highlights the main distinctives of the three branches. In using this chart, it is important to understand that Judaism, in all its branches, is a religion of deed, not creed. It is possible to be an atheist and yet an Orthodox Jew! One may identify oneself as Orthodox because of attending an Orthodox congregation or because one keeps a traditional Jewish lifestyle (observing the Sabbath strictly, keeping kosher, etc.). What one believes about God, sin, or the afterlife is not nearly as important as living a proper life here and now, as defined by the branch to which one belongs. We can say that it is probable that someone who is Orthodox will in fact believe in God, while an atheist would be more likely to align with the Reform branch, if any. But there are many exceptions. Though one can pair doctrinal positions with the three branches, doctrine is not taught in Judaism as it is in Christianity, and one may easily adhere to a particular branch without adopting the doctrines of that branch.

In other words, one can surmise correctly what an individual’s lifestyle is likely to be on the basis of the branch to which he or she adheres. The only way to find out what a Jewish friend believes, however, is to ask. Do not assume what his or her beliefs are on the basis of the branch with which he or she affiliates.

Other Kinds of Judaism

The following are not major branches but should be known:

Reconstructionist

Reconstructionist Judaism is an American offshoot of Conservative Judaism. It maintains that Judaism is a “religious civilization” that must constantly adapt to contemporary life.

Hasidic

Hasidic Judaism, usually called Hasidism, is an ultra- Orthodox movement characterized by strict observance of the Law of Moses, mystical teachings, and is socially separatist. Several different Hasidic groups exist. Each finds its identity in its leader, called the rebbe, who is the dynastic head of the particular Hasidic group in which leadership is passed down through the generations from father to son.

Zionist

Zionism is listed here because it is sometimes mistaken as a form of Judaism. In reality it is a political movement dating from the late 19th century, concerned with the return of Jews to the land of Israel.

Beliefs and Practices

Beliefs

Above we referred to the fact that Judaism is a religion of deed, not creed. If there is any religious principle (what Christians would call a “doctrine”) that Judaism explicitly affirms and teaches, it is the “unity of God.” Deuteronomy 6:4—called the Sh’ma—proclaims: “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.” Beyond the affirmation of the Sh’ma, there have been attempts at compiling various statements of faith (such as the Thirteen Principles of Maimonides), but they have been few and not widely studied or accepted as binding.

The three branches do have their more or less “official” doctrinal positions on various matters such as the person of God or the nature of humankind. These are described in the chart of “The Three Branches of Judaism.” In no way, however, are they binding on any Jewish person.

Practices

The Annual Holiday Cycle

Almost all Jewish people, regardless of the branch to which they belong, observe at least some of the Jewish holidays. Two notes on terminology: Jewish people usually speak of “observing” the holidays rather than “celebrating” them. And while it is common for Christians to speak of the “feasts of Israel,” they are spoken of by Jewish people as the “Jewish holidays.” The major holidays in Judaism are explained on the chart on page five.

The Life Cycle

Besides the annual holidays, there are various distinctive lifestyle events that characterize the lives of most Jewish people. Three of them are mentioned here. Consult resources in the bibliography to learn about the others.

• Circumcision of sons on the eighth day. The accompanying ceremony is called brit milah.

• Barmitzvah(forboys)andbatmitzvah(forgirls—nottradi- tional). The coming of age ceremony at age 13. Generally consists of a synagogue service followed by an extended and elaborate reception with full meal.

• Jewish weddings are typically characterized by theceremo-ny under a canopy (the chuppah, rhymes with “look, a wedding!” and the “ch” is pronounced gutterally as in German) and the smashing of a glass wrapped in a cloth to symbolize the destruction of the Temple.

The Jewish Scriptures

The Old Testament portion of the Bible is the Scripture of Judaism. Some Jewish people prefer the term the “Hebrew Bible” so as not to imply that they accord any validity to the idea of a “new” covenant in contrast to an “old” one. In practice, however, many do use the term “Old Testament.” It should be noted that even though many Jews do not consider the Old Testament to be the Word of God and inspired, it is generally accorded respect as part of Jewish tradition and history.

There are other books, such as the Talmud, considered by Orthodox Jews to possess divine authority. The Talmud consists of the Mishnah and the Gemara. The Mishnah consists in large part of various legal rulings and was compiled around A.D. 200. The Gemara elaborates and comments on the discussions in the Mishnah and was compiled around A.D. 550. Most Jewish people consider the Talmud and other rabbinic interpretations to be useful for ethics and instructive for life but not binding as divine authority.

Approaching Jewish People with the Gospel

How Jewish People View the Gospel

“Christianity is for the Gentiles”

Christianity is considered to be “their” religion. It is perfectly fine for Gentiles to believe in Jesus. Jews, however, neither need to nor should they consider Christ. If a Jewish person is considering any religion, it should be Judaism. Furthermore, a Christian is considered to be any Westerner or churchgoer who is a Gentile. Since Jews are Jewish by virtue of birth, they assume that Christians are those born into a Christian home. The idea of a personal faith commitment is not understood.

You can respond by explaining that even though you were born a Gentile, you had to become a Christian by personal faith in Jesus. A Christian does not mean a follower of a Gentile religion but rather someone who is a follower of the Jewish Messiah—and “Christ” is Greek for “Messiah.” You can further underscore the Jewishness of what you believe by explaining that by believing in Jesus, you came to believe in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the three patriarchs of the book of Genesis.

The Unspoken Objection

There is one underlying objection that almost all Jewish people have concerning placing one’s faith in Jesus: that it is not a Jewish thing to do, that they will cease to be Jewish if they believe in Jesus, and that becoming a Christian means turning one’s back on one’s people, history, and heritage. In addition, many Jewish people fear the social consequences that they would experience should they come to faith in or even consider Christ.

“Jewishness is a Way of Life.”

Whether or not a Jewish person adheres to some form of Judaism, his or her Jewishness is a way of life to be lived out in varying degrees. There are Jewish ways of thinking and doing that differ from Gentile ways. To a Jewish person, Gentiles can seem puritanical in dress and behavior, subdued in interpersonal communication, overly conservative in politics and lifestyle. Church services differ considerably from synagogue services, and church hymns are much different than the haunting chant of a cantor or the jazzy sound of an East European klezmer band. To a Jewish person, being a Christian means identifying with a way of life different than the Jewish one.

A Jewish friend needs to be encouraged that in following Jesus, he or she does not abandon Jewish identity. Perhaps your friend would be willing to meet with a Jewish believer in Jesus, or to read the story of a Jewish person who came to faith in Jesus (see the bibliography for testimony resources).

Jews Presume a Standing with God

Jews do not speak of “salvation,” for there is nothing to be saved from. If there is a God, then Jewish people already have a relationship with Him. Jesus is superfluous for Jews.

In spite of these views, Jewish people are continuing to come to the Lord in record numbers. Many have come to faith through the witness of a Gentile Christian. The following sections can help you more effectively witness, both by showing what you might avoid and the positive things you can do.

Avoid certain offensive words. The Gospel will always offend because of the message of the cross, since none of us like being told we are sinful. However, there are other points at which Jewish people can take offense or exception. It is not necessary to be rigidly on guard, but one can avoid unnecessary negative emotional overtones if one chooses certain words rather than others.

First, avoid Christian jargon in general. Some Christians speak in a language that carries little meaning for the unchurched: “the precious blood of our Lord Jesus Christ,” “saved” and “born again” all carry meaning for the Christian but not for the average secular or Jewish person.

Second, avoid certain terms and utilize others.

• “The Jews” or “you Jews” sounds anti-Semitic on the lips of a Gentile (though Jewish people will refer to “Jews” when speaking among themselves). It is better to say “the Jewish people.” “A Jewish man” is better than “a Jew.” “How do Jewish people observe Passover” is a better question than “What do Jews do at Passover” which has an alienating sound to it. Also do not call a Jewish woman a “Jewess” but “a Jewish woman.” And do not call the Jewish people “Hebrews.” That term was in use among the Jewish people a hundred years ago but not any longer.

• “Jewish” is a word that should be used only to describe people, land, religion, or language. If you refer to “Jewish money” or “Jewish control of the media,” you may well be harboring anti-Semitic attitudes.

• It is best to avoid the terms “missionaries” or “mission.” They tend to connote rescue missions that help derelicts, or those who work overseas among primitive peoples, or even worse, those who are paid to “snatch Jewish souls.”

“The cross” symbolizes persecution for many Jews. It is better to speak about “the death of Jesus.” “Convert” also implies leaving behind one’s Jewishness. It is better to speak about “becoming a believer (or follower) of Jesus.” But it is appropriate to explain that biblical conversion was spoken of by the prophets as meaning “turning back to God” rather than “changing one’s religion” (see, for example, Isaiah 44:22; Jeremiah 4:1; 24:7; Joel 2:12).

Some suggest replacing the name “Jesus” with the Hebrew equivalent of “Y’shua.” While it is good to refer to “Y’shua”—and explain that such is his Hebrew name—no one will realize that you are referring to the historical person Jesus of Nazareth unless you also use “Jesus”! In today’s climate, the name, Jesus, does not provoke as negative a reaction as it once did. Also, it is preferable to speak of “the Messiah Jesus” rather than “Jesus Christ.” Many Jews do not realize that “Christ” means “Messiah” and think that “Christ” was His last name!

Finally, Jewish people enjoy telling Jewish jokes to one another, but a non-Jew should not do so. Many Jewish people will not know how to respond and will think you are ridiculing them. Similarly, do not criticize leaders in the Jewish communi- ty. Though no person in this world is above reproach in all things, let any justified criticisms come from Jewish people rather than from you.

Above all, however, remember that the Gospel can be inherently offensive! If someone takes exception to your witness, it may well be because they are taking exception to God.

Don’t succumb to the fallacy of only showing love. Some Christians never voice the Gospel to Jewish friends because they fear a negative response. So they reason that they will “show love” to their friends and be a witness in that way. Of course, Christians should always show love to people. It is wrong, however, to imagine that you will “love someone into the Kingdom.” Jewish people are already morally upstanding by general community standards. Most are “nice” people; many give to charitable causes. Simply living a life of love will not convey the saving Gospel. Rather, one must verbalize the Gospel, which can be done in the following way.

Some Things to Do in Witnessing Situations

Witness to Friends Who Are Jewish

It is a good idea to witness primarily to Jewish people with whom you’ve established a friendship. You can ascertain if a friend is Jewish by the holidays he or she observes, or perhaps by whether he or she wears a Star of David around his or her neck as jewelry, and often by the surname. Then, it is important that you let the person know that you know he or she is Jewish. This is best done not by directly telling them, but in relationship-building ways such as sending Jewish holiday greeting cards at the appropriate time (see the chart on the Jewish holidays). Doing this not only clears the ground by letting the person know you recognize that they are Jewish, but it is also a good way to continue to cultivate a friendship with someone Jewish.

Move to Spiritual Topics

Generally, we can be bolder in witnessing to a friend than to a stranger.

Often a holiday season is an excellent time to initiate a witnessing conversation. You might ask your Jewish friend to tell you something about what his or her Passover was like, or about Hanukkah.

Then you might try to initiate a conversation. This should be done in a way that is natural for you. One way that works for some is by saying something surprising yet direct and then following it up with a question: “As a Christian, I’m discovering that our faith is basically Jewish. I guess you could say that I believe in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Why do you suppose it’s mostly Gentiles who believe in Him even though Christianity is basically Jewish?” Let him or her respond and lead into a conversation.

Jewish people frequently employ humor in discussing spiritual matters, so you could say something like, “We just had Easter which celebrates the resurrection of Jesus. Since we believe He rose from the dead and is still living, do you suppose we can say that He is the oldest Jewish person alive?”

If the chemistry of your relationship with a Jewish person is right, you can offer a challenge: “Let me ask you something. I believe in Jesus and you don’t. And as Christians, we think we should be telling everyone about God and about Jesus. If you were me, how would you talk to (a basically non-religious person like yourself, an Orthodox Jewish man like yourself, an atheist like yourself) about the Bible and Jesus?”

These are not persuasive statements, but remarks and questions designed to be an invitation. The person might respond by saying, “It would be impossible for me to believe in Jesus,” or “I don’t want to talk about that.” Accept the answer, and if they are not willing to hear more, don’t proceed. (If asked, however, it is appropriate to explain why it is that Christians consider it important to tell others about God.) On the other hand, you may encounter curiosity and a desire to hear more.

Use a Jewish Frame of Reference

If you receive a positive response, you can continue to talk about the Gospel in a Jewish frame of reference. For example, you can tell a Jewish friend how, when Jesus observed—a more Jewish expression than “celebrated”—the Last Supper, it was really a Passover seder. Although the ceremony has been expanded since the time of Jesus, the disciples and Jesus observed what was at that time the full order of service for Passover night (Luke 22:7-20).

One of the parts that was added after the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70 has to do with the three unleavened wafers (matzo) (see Rosen, Christ in the Passover). The three wafers are placed in a silk container called a matzo tash, which has three compartments, one for each wafer. Or, they are stacked on a plate with napkins separating them and covered with a cloth. The three wafers symbolize unity.

During the course of the ceremony, the host removes the middle wafer from the silk bag, breaks it in half, and puts one of the halves back in the matzo tash. He then wraps the other half in a napkin, puts it in another white silk bag, and hides it. This hidden wafer is called aphikomen (“after dish” or “that which comes last”).1 After the meal, the children make a game of looking for the aphikomen while the parents guide them. When found, the host breaks the wafer and distributes the pieces to the others, who eat the wafer with an attitude of reverence.

Ask your Jewish friend why the middle wafer is removed and not one of the others. Why is it broken? Also, why hide it and then bring it back into the ceremony later?

Could it be that this ceremony is more than what the contemporary seder depicts it to be, more than a game? Perhaps it conveys something that most Jewish people do not see. Remarkably, it graphically illustrates the Messiah, that He would have to die (breaking the wafer; Ps. 22; Isa. 53; Dan. 9), be buried (hiding the wafer), and rise from the dead (bringing the wafer back; Job 19:25; Ps. 16:10; Rosen, 1978, 92).

While the Last Supper was indeed an observation of the Passover seder, Jesus was also implementing something new. Luke reports that Jesus “took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me’” (Luke 22:19, emphasis added). God had initially instituted the Passover seder to serve as an annual reminder of how He had redeemed the people of Israel from their bitter slavery in Egypt. Jesus was now saying, though, that they should break the bread “in remembrance of me!” Jesus was indicating that, while the Passover was intended to celebrate how God had won Israel’s redemption from slavery to Egypt, so it was now to also signify the redemption from our slavery to sin that was about to be accomplished through His substitutionary death.

Or, as another way to put things in a Jewish frame of reference, when you speak about sin, you may find a more positive reception during the time of the High Holy Days (see chart of holidays, page five), when most Jewish people, even non-religious ones, attend the synagogue and recite the prayers asking God for forgiveness. Although a Jewish person may try to brush off the idea of sin at other times of the year, most Jews are willing to give it a bit more thought at Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, when Jewish people ask God for forgiveness of any sins committed during the previous year.

Be Clear on Foundational Doctrines

The Gospel is based on the understanding that we are sinners in need of salvation from a savior. These three concepts—sin, salvation, and savior—are foreign to most Jewish people, however, and need to be properly conveyed (see also the “Three Branches” chart).

Sin: Jewish people think of sin in terms of individual deeds, not as a deep-seated characteristic of humankind. The label “sinner” is thought to apply only to notoriously decadent and evil people. You need to point out that all people sin (1 Kings 8:46), using the various biblical analogies. Even the great King David confessed his sin (see Psalm 51). Sin is falling short of the goal, like someone knowing they should be showing love to their chil- dren but are never quite able to do it, or someone who aims to succeed in business but doesn’t quite get there. Sin is the spiritual equivalent of not meeting the goals God has set for us in relating to Him or others (see Romans 3:23). Sin is also like a disease that we need healing from. It is spiritual cancer or AIDS. It is also spiritual pollution that destroys us like smog destroys the ozone layer. Ultimately, sin is going our own way in defiance of God. Sin separates us from knowing and serving God.

Salvation: Salvation is another foreign term to most Jewish people. A common objection is, “Jews don’t believe in salvation.” What is meant is that, “You Christians think we need to be saved from hell in the afterlife, but we Jews are concerned about how to live right here and now.” A helpful entrée is to talk about “redemption” instead of “salvation.” This is a term familiar to many from the Passover seder. You can explain that as God freed the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, so he wants to free us from the slavery to sin in our own lives (Matt. 20:28; Tit. 2:14).

Savior: This is the third term not understood by Jewish people. It can be helpful to speak of a “redeemer” instead of Savior and certainly to use the term “Messiah.”

Putting it together: So rather than stating that“ Jesus came to shed His blood to save us from our sins and be our Savior,” you can convey that “Jesus came to be our Messiah and Redeemer. His death was an atonement for our sins.”

How to Convey Spiritual Truths Using The Bible

Even though not many Jewish people accept the truth of the Old Testament, they do accord it respect. It is good to open the Bible with a Jewish friend and illustrate the Gospel not merely by your statements and stories, but directly by the Word of God.

If you are in your friend’s home, use his or her Bible if he or she has one. It is not that common, though, for the Bible to be a household possession.

Like initiating a conversation, using the Bible should be done only when your friend has indicated a willingness for you to be his or her “teacher” in this regard and for him or her to be your “student.” Otherwise there is the sense that you are speaking from an “invisible pulpit” (Rosen, 1976, 55).

The Bible should be used to raise an issue or to speak to an issue. An example of the first approach is going to the Bible to initiate a discussion of what sin is (Isaiah 53—the suffering servant who takes on the sins of his people; Psalm 51—King David’s confession of sin; 1 Kings 8—King Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the temple). An example of the second approach is going to the Bible in order to answer an objection.

In either case, it is good to begin with the Old Testament portion of the Bible, pointing to certain Messianic prophecies and then to their fulfillment in the New Testament (see the chart of “Selected Messianic Prophecies Fulfilled in Jesus”).

Jesus often talked about how His life was the fulfillment of such prophecies (Matt. 5:17; 26:56; Luke 24:27,44; John 5:37- 40); and the apostles came to see it that way as well (John 2:45; Acts 3:18; Rom. 16:25-26; Heb. 1; 1 Pet. 1:10-12).

Notice in particular the number of prophecies that come from Isaiah 53 (in bold print in the chart). Then, also consider what God says through Isaiah:

Therefore I told you these things [previous prophecies] long ago; before they happened I announced them to you so that you could not say, ‘My idols did them; my wood- en image and metal god ordained them.’ From now on I will tell you of new things, of hidden things unknown to you (Isa. 48:5-6).

Do not be afraid of using the New Testament for more than just fulfillment of Messianic prophecy. You can also use the New Testament to show the Jewishness of the Gospel. For example, Luke2:21 talks about Jesus’ brit milah (ceremony accompanying circumcision); Matthew 26 and Luke 22 show Jesus having a seder; John 10:22 shows Jesus in Jerusalem at Hanukkah, called here by its Greek name of “Dedication.”

Use the concord of spiritual teaching between Old and New Testaments. For example, on the matter of sin you can point to a passage such as Psalm 51 (and compare it with Romans 3:23 in the New Testament). On the idea of a New Covenant prophesied by God, show Jeremiah 31:31-34 (and compare Jesus’ words in Luke 21:20).

Use images from the Old Testament that point to Christ, such as the blood of the Passover lamb being put on the sides and top of the doorframe—a foreshadowing of the cross (Ex. 12:7); the rock that provided water in the wilderness—a foreshadowing of Jesus talking about Him giving “living water” so that those who drink of it would never thirst again (Ex. 17:6; John 4:10-14; 7:37-39; cf., 1 Cor. 10:4); the people of Israel being healed when placing their gaze on the bronze snake at the top of the staff—a foreshadowing of how we are saved by placing our faith in the Messiah who was raised on the cross (Num. 21:8-9; John 3:14); God asking Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, his “only son”—a foreshadowing of how God sacrificed His only Son (Gen. 22:1-18; John 3:16); Jonah being swallowed by a large fish—a foreshadowing of Jesus’ death and resurrection (Jonah 1:17; Matt. 12:40; Luke 11:30).

A helpful hint: Few Jewish people study the Old Testament very much. There is a good chance that you know the Old Testament better than your Jewish friend. And in the event that a question comes up for which you don’t know the answer, you can always say that you don’t know but will look it up. Don’t worry about losing credibility because you don’t have the answers to everything.

Responding to Objections

Undoubtedly the time will come when a Jewish friend will put up objections to the Gospel. In many cases, objections are not thought-out. Raising objections can therefore be a reflex action. They may also represent an “official line” rather than a personally held viewpoint.

“Christians believe in three gods but Jews believe in one God.”

Even an atheist can raise this objection! What is meant may be no more than, “Our religion teaches one God. So even though I do not believe in God, if I did, that is the kind of God I would believe in.” Jewish people understand the Trinity to somehow imply multiple gods. You can simply affirm that you believe that God is One, and point out that Jesus Himself quoted the Sh’ma (the statement of God’s oneness in Deut. 6:4, quoted in Mark 12:29). If your friend pursues the topic by saying, “I just don’t see how God could be three in one—it doesn’t make any sense,” a light response will often answer the question better than an extended theological discourse. For example, you could try saying, “God is bigger than you and me and we’ll never fully understand Him.” This will deflect the conversation from becoming a fruitless discussion of an objection that is being raised more as a smokescreen than out of any real conviction.

“There’s no proof that Jesus was the Messiah.”

This is typically a stereotyped response; the person may never have investigated any of the reasons for faith. Rather than initiate a long argument complete with all kinds of evidence, you might start by asking, “What kind of proof would convince you?” That will raise more specific questions and objections in their mind.

“If Jesus is the Messiah, why isn’t there peace on earth?”

One answer is that we need to have peace in our hearts before there can be peace on earth. Suppose God suddenly declared all wars to cease but that people remained the same. In a short time, we would have the world back again to the way it is now. Put the burden on your friend by replying: “If you seek peace in your own heart first through Jesus, then you can do your part to help make the world a better place.”

“How can you believe in God after all the persecution we’ve been through, not to mention the Holocaust? And it was Christians who did it!”

People can misuse anything, even the Gospel. Tyrants misuse freedom and justice. That doesn’t make freedom and justice any less important to seek after.

As for persecution, that goes all the way back to Pharaoh in Egypt, who obviously was not a Christian. There was persecu- tion even then, and still the Jewish people believed in God.

“The New Testament is anti-Semitic.”

Ask which parts and which passages. Often a person will not be able to point to anything specific. Sometimes a Jewish person will have in mind certain harsh-sounding passages in the Gospel of John and other places, such as John 8:44 or

1 Thessalonians 2:14-16. You can point out that this was the manner of speaking of the prophets of Israel. Isaiah 1 furnishes a good example. Then you should point out that Jesus was not being anti-Semitic but was saddened at the sins of people (referring to all, not just to Jewish people). You can cite the passage at which Jesus weeps over Jerusalem, Matthew 23:37- 39. Point out that you feel similarly about Gentiles who do not turn to God. All have sinned, and God’s response to sin is the same for all people.

“Jews don’t proselytize.”

This objection usually means, “I don’t think people should push their beliefs on others. We Jews don’t, and you Christians shouldn’t either.” You can point out that Isaiah said Israel was to be a light to the nations (Isaiah 42:6; 49:6).2 Moreover, you can say that you don’t believe in forcing religion on anyone either, but you have always found that discussion and persuasion are part of any friendship.

“I’m happy with my own religion.”

You can appropriately respond, “It’s OK if you don’t want to talk about spiritual things, but just remember that the goal of life is not to be happy but to know God. Sometimes what I believe makes me sad because it asks things of me that others might not do. We shouldn’t believe in anything because it makes us happy, but because it’s true. Ultimately, though, knowing the truth about God will bring us complete and lasting happiness and joy.”

“If Jesus was the Messiah, why don’t the rabbis believe in Him?”

The answer is, because he wouldn’t be allowed to be a rabbi much longer! With the kind of community responsibility and weight that a rabbi has, not many rabbis will allow themselves the freedom to ask if Jesus might be the Messiah.

Conclusion

Above all, be encouraged that many Jewish believers in Jesus have come to faith through the loving witness of a Gentile Christian. God can and will use you as you seek to become more familiar with Jewish things and to open up the Gospel to your Jewish friends. The following resources can be a great help.

Bibliography and Resources

Fruchtenbaum, Arnold. Jesus Was a Jew. Tustin, Calif.: Ariel Ministries, 1974.

Frydland, Rachmiel. When Being Jewish Was a Crime. Cincinnati: Messianic Jewish Outreach, 1978.

Goldberg, Louis. Our Jewish Friends. Neptune, N.J.: Loizeaux Brothers, 198).

http://newsaic.com/mwamericanid.html. 5/26/04.

http://www.jewishpeople.net/jewpopofwor1.html. 5/26/04.

Johnson, Paul. History of the Jews. New York: Harper & Row, 1987.

Kac, Arthur. The Messiahship of Jesus: Are Jews Changing Their Attitude Toward Jesus? (revised edition). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1986.

Kolatch, Alfred. The First and Second Jewish Books of Why. Middle Village, N.Y.: Jonathan David, 1981 and 1985.

Questions and Answers from Jews for Jesus. San Francisco: Jews for Jesus, 1983.

McDowell, Josh. Evidence that Demands a Verdict. San Bernardino, Calif.: Campus Crusade for Christ, 1972.

Riggans, Walter. Jesus Ben Joseph: An Introduction to Jesus the Jew. Place not listed: MARC; Olive Press; Monarch Publications, 1993.

Rosen, Ceil and Moishe. Christ in the Passover. Chicago: Moody Press, 1978.

Rosen, Moishe and Ceil Rosen. Share the New Life with a Jew. Chicago: Moody Bible Institute, 1976.

Rosen, Moishe. Y’shua: the Jewish Way to Say Jesus. Chicago: Moody Press, 1982.

Rosen, Ruth (ed.). Testimonies. San Francisco: Purple Pomegranate Productions, 1987.

Telchin, Stan. Betrayed. Lincoln, VA: Chosen Books, 1981.

Telushkin, Joseph. Jewish Literacy: the Most Important Things to Know about the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1991.

The Y’shua Challenge: Answers for Those Who Say Jews Can’t Believe in Jesus. San Francisco: Purple Pomegranate, 1993.

Wylen, Stephen. Settings of Silver: An Introduction to Judaism. New York and Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989.

Organizations

Chosen People Ministries

241 E. 51st Street

New York, NY 10022 (212) 223-2252 www.chosenpeople.com

Friends of Israel

P.O. Box 908 Bellmawr, NJ 08099 (800) 257-7843 www.foi.org

Jews for Jesus

60 Haight St.

San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 864-2600 jfj@jewsforjesus.org www.jewsforjesus.org

Sheresh Ministries

P.O. Box 26415

Colorado Springs, CO 80936 www.shereshministries.org

Lausanne Consultation on Jewish Evangelism

North American Coordinator: Theresa Newell

256 Thorn Street

Sewickley, PA 15143 www.lcje.net LCJENA@aol.com

Endnotes

1. Jewish law professor David Daube thinks the word means “The Coming One” and that the ceremony originally had a messianic implication with a view to the coming Messiah. This may well be the case rather than the traditional meaning of “after dish.” See Daube, He That Cometh (London: Council for Christian-Jewish Understanding, 1966).

2. The “servant” here appears to apply first to Israel, and then to shade off into the Messiah. This issue does not need to be raised in conversation, as one traditional Jewish understanding applies the passages to the nation of Israel. However, the idea of the entire world being blessed through Israel is found as far back as Genesis 12:1-3.

Written by Dr. Rick Robinson, web site coordinator and research librarian with Jews for Jesus. Copyright © 1995, 2004 International Students, Inc.